Navigation / Home / Index / Documents / Photos / Stories / Gravestones / Obits / Generation 10

Boat(w)right Family Genealogy in America

Generation 11

11-1099. NORMAN ISAAC BOATWRIGHT (NORMAN ISAAC7, JAMES W.6, JAMES5, BURRELL THOMAS4, JAMES3, AMBROSE2, Not Yet Determined1) was born 25 Sep 1927 in Augusta, Richmond County, Georgia, and died 17 Apr 1998 in Augusta, Richmond County, Georgia.

Notes for NORMAN ISAAC BOATWRIGHT:

1930 Census: Name: Norman I Boatwright Jr Date: April 9, 1930 Home in 1930: Augusta, Richmond, Georgia Age: 2 Estimated Birth Year: abt 1927 Relation to Head of House: Son Father's Name: Norman I Mother's Name: Julia H Census Place: Augusta, Richmond, Georgia; Roll: 383; Page: 10A; Enumeration District: 1; Image: 21.0.Burial: Westover Memorial Park Cemetery, Augusta, Richmond County, Georgia

11-1100. JAMES BOATWRIGHT (NORMAN ISAAC7, JAMES W.6, JAMES5, BURRELL THOMAS4, JAMES3, AMBROSE2, Not Yet Determined1) was born 11 Nov 1927 in Augusta, Richmond County, Georgia, and died May 1933 in Augusta, Richmond County, Georgia.

Notes for JAMES BOATWRIGHT:

1930 Census: Name: James Boatwright Date: April 9, 1930 Home in 1930: Augusta, Richmond, Georgia Age: 1 Estimated Birth Year: abt 1928 Relation to Head of House: Son Father's Name: Norman I Mother's Name: Julia H Census Place: Augusta, Richmond, Georgia; Roll: 383; Page: 10A; Enumeration District: 1; Image: 21.0.Burial: Westover Memorial Park Cemetery, Augusta, Richmond County, Georgia

11-1101. JAMES KENNERLY BOATWRIGHT (JAMES KENNERLY7, JAMES W.6, JAMES5, BURRELL THOMAS4, JAMES3, AMBROSE2, Not Yet Determined1) was born 04 Oct 1921 in Fulton County, Georgia, and died 08 Apr 1986 in La Grange, Troup County, Georgia.

Notes for JAMES KENNERLY BOATWRIGHT:

1930 Census: Name: James Boatwright Date: April 4, 1930 Home in 1930: La Grange, Troup, Georgia Age: 8 Estimated Birth Year: abt 1922 Relation to Head of House: Son Father's Name: James C Mother's Name: Annie Race: White Census Place: La Grange, Troup, Georgia; Roll 389; Page: 5A; Enumeration District: 4; Image: 196.0. Georgia Deaths, 1919-98 Name: James K Boatwright Death Date: 8 Apr 1986 County of Death: Troup Gender: M (Male) Race: White Age: 64 Years County of Residence: Troup Certificate: 021542 Date Filed: 14 Apr 1986

Burial: Shadowlawn Cemetery, La Grange, Troup County, Georgia

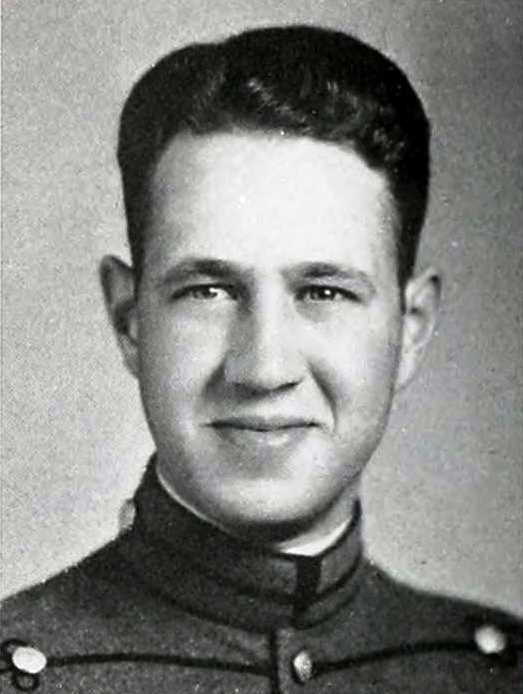

11-1102. PURVIS JAMES "P. J." BOATWRIGHT (PURVIS JAMES7, JAMES W.6, JAMES5, BURRELL THOMAS4, JAMES3, AMBROSE2, Not Yet Determined1) was born 08 Nov 1927 in Augusta, Richmond County, Georgia, and died 05 Apr 1991 in Morristown, Morris County, New Jersey. He married NANCY CAROLYN BLAKELY.

Notes for PURVIS JAMES "P. J." BOATWRIGHT:

P.J. Boatwright was the author of the USGA Rules of Golf.

From the Golf Journal Archives - Golf's Great Losses: P.J. Boatwright Jr.

Mar 12, 2011

The deaths of P.J. Boatwright Jr., and Joseph Dey Jr., have taken two major personalities from the game, and from its traditions that they so strongly upheld.. By Robert Sommers

(Note: This article originally appeared in the May/June 1991 issue of Golf Journal.)

WITHIN A PERIOD of one month, the USGA, indeed all of golf, lost two powerful figures whose influence has been as profound as anyone’s in the long history of the game. Joe Dey died on March 4, and P.J. Boatwright Jr., on April 5.

Since golf became formalized late in the 18th century, no one has claimed such universal respect as these two men for their integrity, their knowledge, and their unyielding devotion to the principles and the traditions of the game.

Each was different in his approach, however; Joe was the more aggressive of the two, the more demanding of those around him, and the more likely to make an impulsive decision concerning the Rules of Golf, and then argue his point until he had convinced himself he was right, and P.J. was the more relaxed, the more forgiving, and perhaps the more thoughtful, a man to whom the rest of the world deferred in matters of the Rules.

In speaking to friends of P.J.at a memorial service, USGA President Grant Spaeth told of a Women’s Open where he approached a player who had hit her ball into a coiled garden hose. Seeing Grant approach, she rose to her full height of perhaps five feet and said to Spaeth, who stands well over six feet, “I don’t want you. I want P.J.”

The two men differed in other respects, Joe’s reputation was based on his perceived excellence as an administrator, although he really wasn’t, as well as on his grasp of the Rules, and a flair for public relations. P.J., on the other hand, wasn’t known as an able administrator, although he was, but more as a force in setting up courses for the USGA’s championships, particularly the Open, and of course for his command of the Rules. Nor did he have Joe’s gift for public speaking, although he did rather well.

There was a further difference. Joe wasn’t a very good player; truthfully, he wasn’t very good at all. P.J., on the other hand, played first-class golf, and indeed played in the 1950 U.S. Open, when Ben Hogan completed his comeback from the automobile accident that almost killed him. P.J. enjoyed telling the story of that Open and the incident on the 14th tee. P.J. had shot 74-75 in the first two rounds, and survived the 36-hole cut. Toward the end of the third round, he was about to play from the 14th tee when Hogan was coming up to the 18th green.

At the Merion Golf Club, in suburban Philadelphia, where the championship was played, the 14th tee stands close to the 18th green. Hogan’s gallery was rushing toward the green when P.J. was preparing to drive. With no regard for the players, the crowd swarmed over the tee and knocked P.J.’s ball from the peg.

A year or so later, when he was playing in a tournament at the Palmetto Golf Club, in Aiken, S.C., he had the opportunity to play with Hogan at the Augusta National Golf Club, shortly before the Masters Tournament. Hogan was at his peak then, but he gave nothing away. Bobby Goodyear, an Augusta member, had arranged the match and invited Bobby Knowles, a Walker Cup player, and Boatwright. As they stood on the first tee, Hogan seemed to know everyone’s handicap, telling each man his figure, and then saying, “And I’m scratch,” an understatement of mammoth proportions.

Hogan arranged the match, taking Goodyear (at 4, the highest handicap) as his partner and stating they would play a $5 nassau. Boatwright felt relieved, since he had only $20. But then Hogan said, “And you, young man, I’ll play you another $5 nassau.” P.J. knew he was in trouble. He shot 74, but Hogan shot 67 and closed him out on the 15th hole. Short of money, P.J. had to borrow what he owed from the caddiemaster.

He often told that story and laughed about it, remembering he was only earning $60 a week, and the match cost him $40.

“But it was worth it,” he sighed.

P.J. Wasn’t in golf administration then. He was working for his father, a cotton merchant. Later he joined the Carolinas Golf Association as its Executive Secretary, where he came under the guidance of Richard S. Tufts, one of the finest golf minds ever associated with the USGA. Tufts’s little 99-page book, The Principles Behind The Rules of Golf, has been a priceless contribution to the game, and the foundation for serious thought concerning the Rules.

P.J. came to the USGA in 1959 as an assistant director, working on the Rules and conducting championships. He ran the Junior Amateur for some years, giving him the opportunity to watch many of those young players who were to become the star players of the future. Frank Hannigan, who like P.J. became the leading executive on the USGA staff, said he was the best judge of young players he had ever known.

Through this period his stature grew both within the USGA and among those he dealt with in Rules matters and in the competitions. Until 1969 his duties at the Open consisted of starting the field from the first tee until the first group reached the 18th tee, then dashing to the final green to take the scorecards.

He often laughed as he told of his first experience at the Open. When Joe told him his duties, P.J. pondered for a moment, then asked, “When do I go to lunch?”

Without pausing, Joe said, “You can probably find a hot-dog stand along the way.”

P.J.’s Open responsibilities grew enormously when Joe resigned to become the Tour’s first commissioner. Now he participated not only in choosing courses for the championships, but also in setting them up. He also became the ranking Rules authority on the USGA staff.

He became a familiar figure then. No longer confined to the scorer’s tent (Hannigan filled that role for a time), P.J. became more familiar roaming the golf course, a tall, lean, unsmiling figure with slightly slumped shoulders, a flat-topped brimmed hat, hiding behind dark sunglasses. Executive Committee members often joked that when P.J. wore those glasses as he sat in a cart while play flowed past him, he was in truth taking a nap. They delighted when a photographer did indeed catch him with his eyes closed behind the sunglasses, and they had the picture blown up to poster size and unveiled at an Executive Committee meeting.

USUALLY, though, in those early years, P.J. walked with the USGA president, who normally served as the referee with the final group at the Open or the Women’s Open, or the final match of the Amateur Championship. He enjoyed the role. He was with Jack Nicklaus, for example, during the last round of the 1972 Open at Pebble Beach, and commented that Jack played the wrong kind of shot into the 12th hole, a demanding par 3. As P.J. described the shot in an article for this magazine, Jack’s ball “came in hot,” meaning on too low a trajectory, hit the green, and bounded into shaggy rough. From there Nicklaus needed two more shots to work his ball onto the green, then holed an eight-foot putt to save a bogey. He eventually won.

Lyn Lardner was the USGA president at the time, and others around him suggested he was afraid to let P.J. out of his sight in case a Rules problem arose that he couldn’t handle. Lyn wouldn’t deny it.

Soon, though, the committee realized that with P.J. confined to the last grouping, he wasn’t available for other sticky problems that constantly arose, and so his role was changed. He would patrol the course in a cart so that he could rush to other trouble spots.

As P.J.’s prestige grew here, it grew throughout the rest of the world. In addition to his USGA duties, he was appointed secretary of the World Amateur Golf Council when Joe resigned, and became familiar with golf authorities throughout the world. They became familiar with him as well, and as his reputation grew, they deferred to him in most matters concerning the World Amateur Team Championships. Until the last few years, when Michael Bonallack was appointed joint secretary with P.J., he conducted the championships, traveling the world setting up the courses for both the men’s and women’s competitions.

As a matter of fact, he oversaw his last event in New Zealand in October, when the United States won the Women’s World Amateur Team Championship at the Russley Golf Club, in Christchurch, and Sweden won the men’s championship, at the Christchurch Golf Club. The last significant shot he saw was Phil Mickelson’s 40-foot putt for a birdie on the last hole that saved the United States a tie for second place, with New Zealand.

AT ONE TIME or another P. J. dealt with nearly every phase of USGA work. He ran certain championships, became the USGA’s ruling expert on the Rules of Amateur Status, oversaw the handicapping system, and dealt with implements and ball.

When P.J, joined the staff, balls were tested on a crude and often unreliable device set up in the basement of the USGA’s building on East 38th Street, in Manhattan, that would fire the balls at great speed through a tube, where their velocity would be timed with an electrical gadget. A ball would break loose occasionally and ricochet around the room, sending P.J. and everyone else diving for cover.

While he oversaw so many of the USGA’s functions, P.J.’s reputation, though, was based on the Open and the Rules. He was the guardian of tradition in all things related to golf, and especially liked to see narrow fairways and slick, firm greens in the Open. As the 1990 championship approached, he wasn’t satisfied with Medinah Country Club’s greens; he felt they were a touch too soft, but meeting Tim Simpson on the course a day or two before the Open began, he said they’d probably turn a bit more firm by the time the first round started.

Somewhat startled because he thought they felt like iron already, Simpson asked Boatwright, “How do you make rocks hard?” P.J. laughed at that one. He liked to see the greens fast as well; some say too fast. When a staff member argued that greens held to the speed he liked them, perhaps 10 or 11 feet on the Stimpmeter, made putting too important, P.J. argued the opposite, saying a champion golfer should be able to putt fast greens. Losing the argument and growing desperate for some means to save his point, the staff member glared at P.J. and snarled, “You must have been a good putter.”

P.J. turned on that engaging grin and said, “Yeah, I could putt.”

He did have his occasional disputes with Committee members, and he often talked in his sleep. During the Masters Tournament a year ago, Nancy Boatwright, P.J.’s wife of 39 years, came to the breakfast table shaking her head and smiling. Asked to explain, she said P.J. had just blurted out in his sleep, “All right, turn it into a pitch-and-putt course.” Then she laughed and said, “He’s arguing with Judy Bell about the Women’s Open.” P.J. and Judy, an Executive Committee member, set up the Women’s Open course together.

Boatwright was honored frequently, most recently receiving the 1990 William D. Richardson Award for distinguished contributions to golf, given by the Golf Writers Association of America. He also received the Metropolitan (N.Y.) Golf Association’s Distinguished Service Award, in 1983, and the Metropolitan Golf Writers Association’s 1986 Gold Tee Award.

P.J. was a quiet, somewhat studious, impeccably dressed man who slouched through the halls of the USGA in a slow-paced gait, poked his head through an office door and without fail called the occupant by his last name, held a brief conversation in his soft Southern voice, then ambled off, probably back to his office in the center of the third floor. Those of the staff will remember him setting behind his uncluttered desk, drawing on his pipe, grappling with a problem concerning the Rules.

THIS IS also the vision held by Spaeth. Speaking of an early meeting with P.J., he said, “About 12 years ago I paid a courtesy call on P.J. at Golf House. He was sitting at his desk with his books puzzling by himself over a Rules problem. How remarkable, I’ve mused ever since that this quiet man from places I don’t know – Aiken, Spartanburg – achieved such a dominant position and presence. Indeed, I came to feel he had the attributes of a superb jurist, certainly those of a statesman.

“First and foremost, he understood his charter – the preservation of the traditions and values we inherited from Scotland, with heavy emphasis on the individual responsibilities of the golfers. He learned from his mentor, Dick Tufts, but it was P.J.’s hand that steered us so carefully. He was obviously a caring expert, but he was a craftsman as well, carefully identifying the issues, and then interpreting and drafting with clarity and skill. He understood that defining the game by means of the Rules would succeed only if they made sense, they were understood, and they were accepted by golfers. His explanations and justifications were compelling.

“There was never a hint of impatience or arrogance. For the volunteer Committeeman who advanced an idea, he would pause, maybe draw on that pipe, then he might drawl, ‘Grant, I think you may have something there.’ Those were special moments.”

P.J. was 63 when he died. He had planned to make the 1992 Open his last, retire, move to Charleston, S.C., buy a boat, and spend the rest of his days fishing.

All Right With Boatwright

P. J. Boatwright, replacing Joe Dey, will direct the U.S. Open

Curry Kirkpatrick

When Joseph C. Dey Jr. resigned last January as executive director of the United States Golf Association a good many people-some but not all of them outside the hallowed grounds of the golf establishment-wondered if the power and glory of the USGA might go right along with him. It was not an unreasonable reaction. For 34 years-since Dey joined the organization, whose staff, at the time, consisted of himself and two secretaries working in two rooms over a bank in New York City-the USGA, in the public mind at least, was Joe Dey.

In his three decades as potentate of amateur golf Dey was the force behind much of the growth and improvement in the organization of the game: the membership roster of the USGA quadrupled to more than 3,700 clubs; the number of annual championship tournaments conducted by the association was raised from four to nine and the international competitions from two to six; and the prize money in the U.S. Open multiplied 40-fold, from $5,000 in 1934 when Olin Dutra won at Merion to $200,000, the figure that will be divided up in Houston this week. Dey was also responsible for moving the USGA into the publications business, into movie production and, most important of all, out of its parochial Eastern attitudes. He invested it with a laudable sense of geography. In 1936 all four USGA championships-the Open, Amateur, Women's Amateur and Public Links-were played within the Metropolitan New York area. This summer the nine championships are dispersed in equal measure across the land from Erie, Pa. to Spokane.

All of this done, Dey left four months ago to become the much-heralded "czar" of the PGA tour and, as will happen when monarchs of like reputation depart (will the FBI lose the trail when J. Edgar quits?), serious questions regarding the future welfare of amateur golf were in order. But while heavy rains have taxed the drainage system of the basement at Golf House (the charming town-house headquarters of the USGA in Manhattan) and while just the other day a man delivered burial flowers to the place thinking it a funeral home, the USGA is-honest-alive, well and in the capable hands of P. J. Boatwright Jr. ("All right with Boatwright," as they might, but don't, say in the quiet rooms of Golf House.)

P. J. Boatwright Jr. is a tall (like Joe Dey), handsome (like Joe Dey) man, with a lofty, dignified manner (like Joe Dey), who wears the muted suits and button-downs of Brooks Brothers (like Joe Dey) and handles his position with a strict adherence to The Right Way of Doing Things (just like Joe Dey), which is all as it should be. He has been Dey's assistant for nine years, studying at the knee of the master, learning the nuances of the organization and its main job, preparing himself and specializing in interpretation of the Rules of Golf. He was a participant in the last two quadrennial conferences between the USGA and the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St. Andrews (the only other rule-making body in the world) and has drafted most of the rule decisions handed down by the USGA in recent years.

Though Boatwright's name is not a clubhousehold word, this is a year for that kind. P. J. ("Purvis James-I don't usually tell people that") is known well enough in the circles that count. He has been making speeches throughout his tenure as assistant director of the USGA so that officers of state golf associations easily identify with him. He has been the presiding USGA staff member at the annual Boys' Junior tournament, so many of the younger pros on the tour remember him. And anyone who has played in a U.S. Open in the past nine years also would recognize P. J. Boatwright. His was the voice that said "Play away, please" on No. 1 and his the hand that took the scorecards on No. 18. In toto, P. J. Boatwright has been there.

Additionally, Boatwright is probably the best player ever to hold a high office in golf's officialdom. A native of Augusta, Ga., he developed into a fine amateur while a student at Wofford College in Spartanburg, S.C. In the 1950s he won the Carolina Open twice and Carolina Amateur once. He holds two of the five course records at Pinehurst. He was medalist in the 1948 Southern Intercollegiate over such names as Art Wall and Mike Souchak and later appeared in three U.S. Amateurs and the 1950 U.S. Open at Merion, where he made the cut despite a 6 on the opening hole and a near trampling later at the 14th.

"I had my ball up and ready on 14 tee," Boatwright recalls, "and then here came Ben Hogan, the year of his great comeback, up the 18th. There were no ropes up then, and Hogan's gallery stormed over the tee, knocked my ball down and just about chased me off the course." Boatwright, 41, now lives with his wife Nancy, their son and two daughters in Westport, Conn., a grand bastion of social credentials situated on Long Island Sound and featuring a community-owned golf club-Long Shore-where P. J. does not often get time to play anymore. His handicap still hovers around 3, but he is more interested these days in the development of his 13-year-old son, Purvis James Boatwright III, who took up golf last year and now shoots in the 70s.

In the soft, mellow tones of his native South, Boatwright talks of his new position with little awe but great respect for his predecessor, Dey. "I think my influence will be the same as Joe's was," Boatwright says, "and I mean right away. It's the nature of the job."

Frank Hannigan, the assistant director of the USGA, sees the positions of the two men in similar terms. "It's all a matter of timing," he says. " Joe Dey grew up with the organization. He was the whole show at first, then he built it up into this huge, diversified program. I think Joe will agree he was not a singularly powerful guy; power is a matter of confidence. He stood for the USGA, and it was easy to focus on him. In time P. J. will stand for the association. It may not be the same, but remember, when Joe Dey was P. J.'s age he wasn't Joe Dey yet either."

More than anything else, the change has brought about a more relaxed atmosphere around Golf House and probably will do so in future USGA tournaments also. For all his brilliance and devotion, Joe Dey was a stiff, hard taskmaster. Presumably no more will staff members have to hurry across town to beat their lunch-hour deadlines nor press photographers have their armbands ripped from their coats (along with half their sleeve) for indiscretions at a big tournament. (Dey became so angry at the inertia of a scorekeeper at the Women's Open one time that he rushed up on her platform too fast, slipped off and broke his arm.)

P. J. Boatwright is not likely to get that worked up. As one USGA member put it, "The golf establishment feels he's the right man at the right time. Everything is just fine. God's in his heaven, P. J.'s head of the USGA and all is right with the world."

See? All right with Boatwright.

In 1991, the USGA established the P.J. Boatwright, Jr. Internship Program. This program is

designed to give experience to individuals who are interested in pursuing a career in golf

administration, while assisting state and regional golf associations, as well as other non-profit

organizations dedicated to the promotion of amateur golf, on a short-term, entry level basis.

Each internship is unique, since the needs of each association are different. An intern may help

conduct tournaments, junior golf programs, membership services, and other general activities that

promote the best interests of golf. Arrangements for multiple summer employment are possible as

well.

The common thread, which runs through most internships, is exposure to tournament preparations, tournament administration and post tournament business. The nature of tournament administration will test one's patience, initiative and decision-making abilities, as well as one's ability to endure long hours and hard work.

A prospective intern should demonstrate strong managerial potential and a sufficient interest in golf. Golf associations that participate in the Internship Program will provide an appropriate level of orientation and ongoing training and attention.

The Gettysburg Times Newspaper

August 23, 1963, page 16

New Jersey Golf Course is Lighted

By Will Grimsley, Associated Press Sports Writer

Sewell, NJ AP - Okay, so night time golf is here. Now what? "We won't play the National Open under arcs any time soon," said P.J. Boatwright, assistant executive director of the U.S. Golf Association. "It's interesting and it's fun, but you can't expect it to take the place of daytime play. Night golf should lend itself particularly to the overcrowed public courses. It has it's problems." added Fred Corcoran, Tournament director of the International Golf Association. "I remember I predicted back in 1939 that golf courses one day would be lighted, but it will be a few years before this becomes a general fad." Boatright and Corcoran were two of the many golf personalities invited to Tall Pines here this weekend to see a bit of golf history made - lighting of the first regulation course.

At a cost of $63,000, 121 powerful mercury floodlights of 1,000 watts each have been mounted on 76 - 40 foot wood poles around the nine hole course, pouring out light equal to the flame of six million candles. Although driving ranges and minature layouts and some 200 sporty par three courses are illuminated for night play, this is the first man-sized course to beat the darkness barrier. Tall Pines, a private club, has holes comparable to those the pros play on tour, with 28 deep sand traps, 1,000 added trees and out-of-bounds on five holes.

A par-five hole stretches 520 yards. A valley par-four reaches 420 yards, and another 415 yards. There is a par-three of 215 yards. Played twice around, it measures 6,460 yards with par 35-35 - 70. "It's not daylight, but it is the nearest thing to it and the best money can buy." said owner of the little private club, Peter McEvoy, Sr. Larry Dengler, marketing engineer for the electrical concern which installed the system, predicted there would be a mass movement toward lighted courses, with muncipal courses in the vanguard.

The New York Times

January 6, 1991

SPORTS PEOPLE; In the Hospital

On Friday, P. J. Boatwright, the executive director of rules and competitions for the United States Golf Association, was admitted to Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in Manhattan. Boatwright went to see doctors late last year for what was suspected to be a herniated disk, but a malignant tumor was found on his spine. After the tumor was removed, another malignancy was found several days later.

Boatwright, 63 years old, writes and interprets the rules of golf and is widely considered the game's foremost rules authority. He also oversees the course setup of the sites of the U.S.G.A.'s championships, which include the United States Open.

The mystery of Hogan's 1-iron

SO, WHATEVER happened to Ben Hogan's 1-iron?

Well, nobody knows for sure. And never will. All we do know is that somewhere between the fourth round of the 1950 U.S. Open and the next day's 18-hole playoff, it went missing. Along with his shoes, as it turns out. And it remained that way for more than three decades.

In 1973, the executive director of the USGA, P.J. Boatwright Jr., wrote to Hogan asking if he would donate the club to the association's museum. That's when Hogan finally admitted he didn't have it.

Ten years later, club dealer Bobby Farino purchased an old set of MacGregor woods and matching irons for $150 at The Players Championship. Later he found another club, a 1-iron with "Hogan Personal Model" stamped on the face. Priceless.

Farino told former Wake Forest basketball player/coach Jackie Murdock, who was friends with fellow Demon Deacon Lanny Wadkins. So Wadkins, a native Texan like Hogan, was entrusted with returning it to the man who made it famous.

"You could tell it was [Hogan's]," Wadkins said. "If you looked at his equipment, there were giveaways. The flat lie, the firm shaft, the grip. He had a very special way of doing things, especially when it came to his clubs. It all had to be just right.

"He was working in his office when I took it over to him. He knew as soon as he saw it. I said, 'I think I have something that belongs to you.' And he said, 'I haven't seen this in a long, long time.' He couldn't believe it. It was pretty amazing."

Not long after that, Hogan gave it to the USGA for safekeeping. It has been with the USGA ever since. It was brought to Merion 2 months ago for U.S. Open media day. In some ways, it has never left.

Source: Mike Kern

Posted: June 10, 2013

1930 Census: Name: Purvis J Boatwright Jr Date: April 15, 1930 Home in 1930: Augusta, Richmond, Georgia Age: 3 Estimated Birth Year: abt 1927 Relation to Head of House: Grandson Father's Name: Purvis J Mother's Name: Louise Census Place: Augusta, Richmond, Georgia; Roll: 383; Page: 19A; Enumeration District: 3; Image: 121.0. Social Security Death Index Name: P. J. Boatwright SSN: 251-44-1545 Born: 8 Nov 1927 Died: Apr 1991 State (Year) SSN issued: South Carolina (Before 1951)

Children of P. J. BOATWRIGHT and NANCY BLAKELY are:

i. CYNTHIA BLAKELY BOATWRIGHT.

ii. PURVIS JAMES BOATWRIGHT.

11-1103. WALTON LOUISE BOATWRIGHT (PURVIS JAMES7, JAMES W.6, JAMES5, BURRELL THOMAS4, JAMES3, AMBROSE2, Not Yet Determined1) was born 08 May 1929 in Augusta, Richmond County, Georgia.

Notes for WALTON LOUISE BOATWRIGHT:

1930 Census: Name: Wallen L Boatwright Date: April 15, 1930 Home in 1930: Augusta, Richmond, Georgia Age: 4 months Estimated Birth Year: abt 1930 Relation to Head of House: Granddaughter Father's Name: Purvis J Mother's Name: Louise Census Place: Augusta, Richmond, Georgia; Roll: 383; Page: 19A; Enumeration District: 3; Image: 121.0.

11-1104. MARTHA BOATWRIGHT (JAMES7, JAMES W.6, JAMES5, BURRELL THOMAS4, JAMES3, AMBROSE2, Not Yet Determined1) was born 1928 in Augusta, Richmond County, Georgia.

Notes for MARTHA BOATWRIGHT:

1930 Census: Name: Martha Boatwright Home in 1930: Augusta, Richmond, Georgia Age: 2 Estimated Birth Year: abt 1928 BirthPlace: Georgia Relation to Head of House: Daughter Census Place: Augusta, Richmond, Georgia; Roll: 383; Page: 4B; Enumeration District: 9; Image: 586.0.

11-1106. MARY L. BOATWRIGHT (CLIFFORD BEDELLE7, CLIFFORD BEDELLE6, ELIJAH5, BURRELL THOMAS4, JAMES3, AMBROSE2, Not Yet Determined1) was born 1923 in South Carolina.

Notes for MARY L. BOATWRIGHT:

1930 Census: Name: Mary L Boatwright Date: April 4, 1930 Home in 1930: Spartanburg, Spartanburg, South Carolina Age: 7 Estimated birth year: abt 1923 Relation to head-of-house: Daughter Father's Name: Clifford Mother's Name: Louise J Census Place: Spartanburg, Spartanburg, South Carolina; Roll: 2213; Page: 3B; Enumeration District: 45; Image: 447.0.

11-1107. FRANCES J. BOATWRIGHT (GREER BAUGHMAN7, EDMUND PENDLETON 6, JOHN LORD5, JOHN HENRY4, JAMES3, AMBROSE2, Not Yet Determined1) was born 1922 in Richmond, Virginia, and died 2000 in Richmond, Virginia.

Notes for FRANCES J. BOATWRIGHT:

1930 Census: Name: Frances J Boatwright Date: April 11, 1930 Age: 7 Estimated birth year: abt 1923 Relation to head-of-house: Daughter Father's Name: Greer B Boatwright Mother's Name: Myrtle W Boatwright Home in 1930: Richmond, Richmond (Independent City), Virginia Census Place: Richmond, Richmond (Independent City), Virginia; Roll: 2474; Page: 19B; Enumeration District: 105; Image: 772.0.

11-1108. ANN J. BOATWRIGHT (GREER BAUGHMAN7, EDMUND PENDLETON 6, JOHN LORD5, JOHN HENRY4, JAMES3, AMBROSE2, Not Yet Determined1) was born 1924 in Richmond, Virginia.

Notes for ANN J. BOATWRIGHT:

1930 Census: Name: Ann J Boatwright Date: April 11, 1930 Age: 5 Estimated birth year: abt 1925 Relation to head-of-house: Daughter Father's Name: Greer B Boatwright Mother's Name: Myrtle W Boatwright Home in 1930: Richmond, Richmond (Independent City), Virginia Image source: Year: 1930; Census Place: Richmond, Richmond (Independent City), Virginia; Roll: 2474; Page: 19B; Enumeration District: 105; Image: 772.0.

last modified: March 17, 2014

URL: http://www.boatwrightgenealogy.com

Navigation / Home / Index / Documents / Photos / Stories / Gravestones / Obits / Generation 10